Creating a Coder experiment from scratch (tutorial)#

In the previous tutorial, we discussed most of the “administrative” stuff that needs to happen in any PsychoPy experiment and explained some basic features (clocks, responses). In this tutorial, we’ll discuss how to actually add components to the experiment, interact with user responses, and work with user data. There are a lot of optional, more advanced topics/sections in this tutorial, so feel free to skip those if you are short on time.

Warning

PsychoPy is an incredibly versatile and flexible software package. The “downside” of this is that sometimes the same thing can be achieved in multiple different ways. In this tutorial, we’ll highlight different approaches when appropriate, but remember that almost always these approaches are functionally equivalent, so it’s up to you which approach you use!

We of course assume you finished the previous tutorial already. In this tutorial, we are going to continue our experiment with what we ended up with from the last tutorial. If you want, you can copy the (correct) code from the previous tutorial below, which we’ll extend in this tutorial.

Click to reveal the template!

from psychopy.gui import DlgFromDict

from psychopy.visual import Window

from psychopy.core import Clock, quit, wait

from psychopy.event import Mouse

from psychopy.hardware.keyboard import Keyboard

### DIALOG BOX ROUTINE ###

exp_info = {'participant_nr': 99, 'age': ''}

dlg = DlgFromDict(exp_info)

# If pressed Cancel, abort!

if not dlg.OK:

quit()

else:

# Quit when either the participant nr or age is not filled in

if not exp_info['participant_nr'] or not exp_info['age']:

quit()

# Also quit in case of invalid participant nr or age

if exp_info['participant_nr'] > 99 or int(exp_info['age']) < 18:

quit()

else: # let's star the experiment!

print(f"Started experiment for participant {exp_info['participant_nr']} "

f"with age {exp_info['age']}.")

# Initialize a fullscreen window with my monitor (HD format) size

# and my monitor specification called "samsung" from the monitor center

win = Window(size=(1920, 1080), fullscr=False, monitor='samsung')

# Also initialize a mouse, for later

# We'll set it to invisible for now

mouse = Mouse(visible=False)

# Initialize a (global) clock

clock = Clock()

# Initialize Keyboard

kb = Keyboard()

### START BODY OF EXPERIMENT ###

#

# This is where we'll add stuff from the second

# Coder tutorial.

#

### END BODY OF EXPERIMENT ###

# Finish experiment by closing window and quitting

win.close()

quit()

Components#

Like in the Builder, components are the “bread and butter” in the Coder interface as well. In the coder, however, these components are implemented in different classes from the psychopy package. For example, to add a text component, you can use the TextStim class from the psychopy.visual module and to add a sound component, you can use the Sound component from the psychopy.sound module.

Basically, every component from the Builder has an equivalent in the psychopy package. Moreover, each component has largely the same properties in the Builder as in the Coder. For example, the color and font properties from text components in the Builder are also available in the Coder interface as arguments (and attributes) of the corresponding component class. For example, to set the font of a text stim to Calibri and the text color to blue, initialize a TextStim object with font='Calibri' and color=(-1, -1, 1). We won’t discuss all parameters from every component we discuss in this tutorial; you can find all parameters and what they mean in the PsychoPy documentation!

Importantly, all visual stimulus classes (like TextStim, but not Sound) additionally need one (mandatory) argument: a Window object! This allows to TextStim to interact with the window. So, let’s recap: to initialize a component in the Coder interface, we need to (1) import the corresponding class and (2) initialize it with a Window object (in case of visual components) and optionally other arguments that modify the component’s behavior or display.

Now, suppose you would like to welcome my participant by showing a short welcome message — “Welcome to this experiment!”. To do so, you’d need a TextStim which would need to be initialized as follows:

from psychopy.visual import TextStim

# We assume `win` already exists

welcome_txt_stim = TextStim(win, text="Welcome to this experiment!")

ToDo

Paste the code snippet above into your script, after initializing the window and clock, but change the initialization such that the text will be orange and set the font to Calibri. Note: it’s convention to put all import statements together at the top of your script, so make sure the from psychopy.visual import TextStim part is on top of your script as well. Then, run the experiment.

Note: you probably won’t actually see the welcome text (or very briefly)! The reason for this is explained in the next section.

Warning

Like we mentioned in the previous tutorial, if no window opens at all when running your experiment, your script may contain a (syntax) error! In that case, check the Experiment runner window to see what’s wrong!

Note that component properties (such as the text font and color of TextStims) can also be set after initializing the object. Because these arguments are set as attributes during initialization in the __init__ function, you can change these properties by changing the object’s attributes. For example, if you want to change the font size (height) after initialization of a TextStim object, you can do the following:

# Start with a height (font size) of 0.1

some_txt = TextStim(win, "Hello!", height=0.1)

# Later, increase it to 0.2

some_txt.height = 0.2

In the documentation, you may have seen that some attributes can also be changed using a dedicated method, with the same name as the attribute but prefixed with “set”. For example, changing the font size of a TextStim (as in the previous code snippet) could also be achieved as follows:

some_txt = TextStim(win, "Hello!", height=0.1)

some_txt.setHeight(0.2)

It really doesn’t matter which method (setting the attribute directly or using the set method) you use — they do the same thing.

Drawing & flipping#

When running your experiment after including the welcome text component, however, the PsychoPy window does not show the text! As discussed in the lecture, this is because you first need to draw the stimulus! This can be done by calling the draw method that is included in each (visual) component class.

ToDo

After initialization of the text component, call the draw method (without arguments) of the welcome_txt_stim variable. Then, run your experiment.

Argh, still no sign of the welcome text in the window! This is because your monitor contains two buffers, a “front buffer” (which is visible) and a “back buffer” (which isn’t), and components are always drawn on the back buffer! To make the drawn components visible, we need to flip the back buffer to the front, which can be done by calling the flip method of the Window object. By splitting the operation of showing stimuli into two operations (drawing and flipping the back buffer), you can precisely control when you want your stimuli to appear (i.e., when calling flip).

ToDo

Right after the call to the draw method of the text component (welcome_txt_stim), add a call to the flip method (without arguments) of the window (win). Then, run the experiment again.

Finally, you should see the welcome text on the window, albeit quite briefly! Again, it is only shown briefly because PsychoPy will simply follow the script and immediatly go to the next lines (which presumably are those that close the window and quit the experiment, like we discussed in the previous tutorial). There are several ways in which you can specify how long a component is visible, which differ in how precisely they can determine the duration. One of the easiest ways is to add a call to the wait function after the window flip.

ToDo

Using the wait function, make PsychoPy wait for 2 seconds after flipping the window. Then, run the experiment again.

Now you should see that the welcome text is visible for 2 seconds (actually, a bit longer because of the time it takes to shut down the experiment). In one of the next sections, we will discuss other, and more precise, methods to manipulate the duration of stimuli.

Note that after flipping the window such that the back buffer is moved to the front buffer, the back buffer is completely cleared. This means that when you’d flip the window again (without drawing any stuff in the meantime), the front buffer would contain an empty window!

ToDo

After the call to the wait function, flip the window again, and add another call to the wait function for two seconds (otherwise you won’t see the effect of the second flip). Then, run the experiment again.

By flipping the window again, the welcome text disappeared and was replaced by an empty window (because the front buffer was replaced by an empty back buffer). This underlines an important concept: every time you flip the window, you start with an empty back buffer (and you need to draw your stimuli again, if you want to show them again on the next flip).

Responses#

After welcoming our participant, let’s add some instructions. Like we did in the Builder experiment, let’s also make sure that, after reading the instructions, the participant can continue the experiment by pressing enter (“return”). This gives us an excuse to introduce the topic of working with participant responses!

But first, let’s create a TextStim with the instructions:

In this experiment, you will see emotional faces (either happy or angry) with a word above the image (either “happy” or “angry”). Importantly, you need to respond to the EXPRESSION of the face and ignore the word. You respond with the arrow keys:

HAPPY expression = left

ANGRY expression = right(Press ‘enter’ to start the experiment!)

ToDo

Initialize a TextStim object with the text above and store it in a variable named instruct_txt_stim. Make sure it is left-aligned and has a font size of 0.085 (check the docs to see how to do this). Then, draw the TextStim and flip the window to make it visible!

Tip: you can create multi-line strings easily by enclosing text in triple-quotes, e.g., """ some multiline text etc etc """ (more info here). Then, call its draw method, flip the window to make it visible.

ToDo

Using the Keyboard class, make sure the experiment only advances when the participant presses the enter key. Check the previous tutorial if you forgot how to do this!

Timing revisited#

Alright, now it’s time for the most important part of our experiments: the trial loop! Just like the color-word Stroop experiment we implemented in the Builder, we’d like to create a set of trials in our emotion-word Stroop experiment. This also provides us with a nice opportunity to talk about duration and timing again!

Often, you’d like to make sure your trials/stimuli are presented for a specific duration. This is often especially important for perception and psychophysics studies or neuroimaging studies in which you track stimulus processing at high temporal resolution (e.g., EEG/MEG and eyetracking studies).

So far, we only showed you how to use the wait function to control stimulus duration. There are, however, two other and more precise methods, which we’ll call clock-based timing and frame-based timing. We’ll discuss these two methods in turn. But first, let’s discuss how we want to structure our trial.

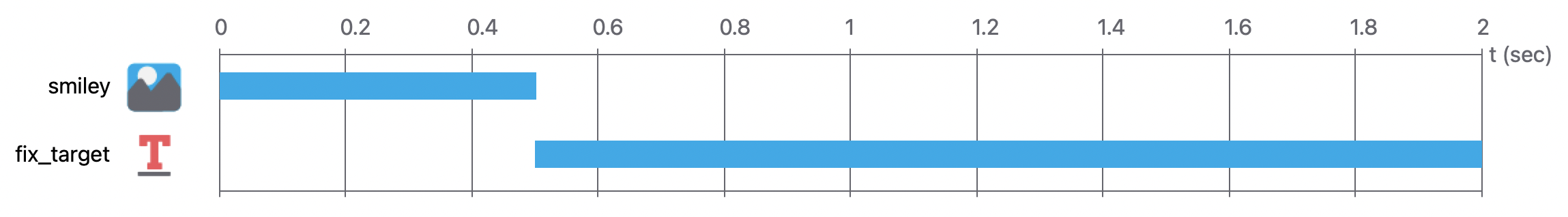

Like we did in the Builder experiment, let our trial routine include the emotion-word stimulus and a subsequent fixation target. Unlike our Builder experiment, let’s only present the stimulus for a fixed amount of time, let’s say 500 milliseconds, which is followed by a fixation cross (a simple “+” sign) for 1500 milliseconds. As such, our trial will take (500 + 1500 = ) 2000 milliseconds; this is sometimes called the inter-trial interval (ITI), i.e., the time from the onset of one trial to the onset of the next trial.Figure 1 shows how this routine would have looked like in the Builder view.

Fig. 1 The trial routine of the emotion-word Stroop experiment.#

As we’re creating an emotion-word Stroop task, we’ll need an image with a emotional facial expression and an emotion word. To create an image, you can use the ImageStim class from the psychopy.visual module. Apart from the mandatory argument win (the current window), it also needs an image (a path to the image file). In the tutorials/week_2 directory, we included two images: angry.png and happy.png. Note that these images are smileys, because it’s really hard to find proper facial expression stimuli without copyright …

ToDo

Import the ImageStim class, initialize an ImageStim object with the angry.png file (store this is in a variable with the name stim_img), and draw it. Also create a TextStim with the word “happy” placed above the smiley (store this is in a variable with the name stim_txt) and draw it. Then, flip the window and run the experiment to see whether it works as expected. You should only see the smiley briefly.

Click here to show the solution (but try it yourself first!)

stim_img = ImageStim(win, image='angry.png')

stim_img.draw()

stim_txt = TextStim(win, text='happy', pos=(0, 0.5))

stim_txt.draw()

win.flip()

Disregarding the timimg issue completely for now, let’s also create a fixation target to show after the smiley.

ToDo

Initialize a fixation target with a “+” sign using a TextStim (store it in a variable named fix_target) and draw and show it after showing the stimulus image (angry.png) and stimulus text (“happy”). Then, run the experiment (you should only see the stimulus and subsequent fixation cross very briefly; we’ll fix that in the next section).

Click here to show the solution (but try it yourself first!)

# This comes immediately after the code from the previous ToDo

fix_target = TextStim(win, '+')

fix_target.draw()

win.flip()

At this point, we haven’t specified for how long we’d like to show our stimulus and fixation target! After showing the stimulus, it will immediately advance to drawing and showing the fixation target (showing both, effectively, for only one frame or “flip”). One way to control this duration is, as discussed before, using the wait function: we could add a call to wait after showing the stimulus (for 500 ms.) and after showing the fixation target (for 1500 ms.). This would definitely work, but the next two sections outline two slightly more precise methods to do so.

Clock-based timing#

In the previous tutorial, we defined a “clock” (using the psychopy.core.Clock class) to do some trivial timing checks, but they can be used in much more useful ways, like controlling the duration of stimuli. We could use the previously defined “global” clock (the clock variable from the previous tutorial) for this, but we’ll actually need that for logging trial onsets later (in an optional section). Instead, let’s create a new Clock object to keep track of the duration of our trial components, which we’ll call trial_clock:

trial_clock = Clock()

At initialization, the clock is at ~0 seconds. Using a while loop, we can use this clock to continuously draw the stimulus (if the clock < 500 ms) or the fixation target (if the clock is between 500 and 2000 ms) and flip the window!

ToDo

Implement the aforementioned while loop in which either the stimulus (smiley and emotion word) or the fixation target is shown, depending on the time since the initialization of the clock (so you need an if-else statement as well)!

Click here to show the solution (but try it yourself first!)

# We assume that the fix_target and stim_txt/stim_img are

# already defined!

while trial_clock.getTime() < 2:

# Draw stimulus or fix depending on time

if trial_clock.getTime() < 0.5:

stim_txt.draw()

stim_img.draw()

else:

fix_target.draw()

# Show whatever is drawn!

win.flip()

You may think: why redraw the components (and flip the window) on every iteration? This is, indeed, not necessary; technically, you only need to draw each component once (the stimulus at 0 ms and the fixation target at 500 ms). However, when programming more complex experiments, you’ll notice that this convention of drawing your components and flipping your windows every iteration actually yields very readable code. Also, (re)drawing the stimuli and flipping the window every iteration does not incur much of a performance hit, as most of the heavy lifting is done by your computer’s graphics card (and not your CPU).

Tip

Instead of re-drawing your stimuli every iteration of the loop across frames, you can also set the attribute autoDraw of visual components to True. This will automatically draw those stimuli upon flipping the window, until you set this attribute to False again!

Frame-based timing (optional)#

Although the clock-based method is reasonably accurate, it implicitly assumes that stimulus duration is continuous, while in reality it is discrete! This is because your monitor “draws” your screen contents at the refresh rate of your monitor. Most standard laptop screens and external computer monitors have a refresh rate of 60 Hz, meaning that it is technically able to redraw the entire screen 60 times per second. The first two minutes of video below explains the concept of refresh rate quite well:

Note that the video also talks about the frame rate (or frames per second, FPS). This concept is related to the refresh rate, but it quantifies how often your screen can actuallly (in reality) be refreshed. Ideally, the refresh rate and the frame rate are exactly the same, but when you’re playing very high resolution video games or are running intricate PsychoPy experiments in which you’re drawing many visual components, your graphics processor may not be able to draw everything in time! When this happens, you’re likely “dropping frames” (for more explanation about this, check out the PsychoPy docs).

The fact that monitors are limited by their refresh rate means that the exact duration of visual stimuli is some multiple of the number of screen refreshes. For example, if you have a 60 Hz screen (which refreshes every 1/60 seconds), a stimulus can be shown for 0.0167 seconds (1/60), 0.0333 seconds (2/60), 0.0500 seconds (3/60), etc. But it cannot be shown for, let’s say, exactly 110 milliseconds.

ToThink

Suppose you want to show a stimulus for 120 milliseconds on a monitor with a refresh rate of 60 Hz. What is the duration closest to 120 milliseconds you can achieve?

Click here to see the answer (but try to come up with the answer yourself first)!

Dividing 120 milliseconds (0.120 seconds) by the refresh rate (1/60) does not result in a whole (integer) number, namely 7.2. This means that 7 frames/flips is the best we can do, which results in 7 * (1/60) = 0.1167 seconds.

So, if you really care about the duration of your stimuli (e.g., in subliminal perception studies), you should specify the duration of your stimuli as a multiple of your refresh rate. Then, to implement this in your PsychoPy script, you can simply draw your stimuli and flip your window as often as the number of frames you want to show your stimuli. For example, if you want to show your stimulus for 60 frames (i.e., 1 second on a 60 Hz monitor), you simply do the drawing + flipping process 60 times!

ToDo

Remove the your clock-based timing implementation (i.e., the while loop from the previous ToDo) and instead program a frame-based timing implementation instead (the duration should be 500 ms for the stimulus and 1500 ms for the fixation target again). Hint: instead of the while loop in the clock-based timing example, you may want to use a for-loop here … Run the experiment when you’re done!

Click here to show the solution (but try it yourself first!)

# We'll assume you have a 60Hz monitor

# 120 frames on a 60Hz monitor is 2000 ms

for frame in range(120):

if frame < 30:

stim_img.draw()

stim_txt.draw()

else:

fix_target.draw()

win.flip()

Tip

For timing precision and preventing dropped frames, it is very important that no other (CPU-heavy) programs are running while you’re running your experiment! So make sure that, when you conduct actual experiments, you shut down all non-essential programs before starting your experiment.

Trial loops#

So far, we only presented a single trial with a emotion word (“happy”) and a(n angry) smiley (i.e., an incongruent trial). Like the color-word Stroop in the Builder tutorial, we’d like to present the participant multiple trials in which the two factors — emotion of the smiley (happy/angry) and the emotion word (“happy”/”angry”) — vary.

So how do we define the different conditions? One way would be two create two lists, one with emotion words and one with the emotion for the smileys, and to choose a random value of each list in each iteration of the trial loop. In our current simple experiment, however, we would recommend to pre-specify the conditions in a CSV or Excel file &mdash just like we did in the Builder tutorial!

ToDo

Create a CSV or Excel file with two columns (named smiley and word) and, let’s say, twenty rows (excluding column names) with either “happy” or “angry” such that there are five trials of each possible emotion-word combination (just like you did in the Builder tutorial). Save it in the same directory as your Python script with the name emo_conditions.xlsx (or emo_conditions.csv). (If you want to see the “solution”, check out the emo_conditions.xlsx file in the solutions/week_1 directory of the course materials).

Tip

Instead of counterbalancing the conditions (here: emotion word and smiley type) yourself, you can use the TrialHandler class from the psychopy.data module, which counterbalances the conditions across trials for you! In addition to simple counterbalancing, this module also contains some very fancy classes for psychophysics “staircases” and such.

To load in the data, we can use our pandas skills! In case of a CSV file, we can use the read_csv function and in case of an Excel file, we can use the read_excel function.

ToDo

Read in your emo_conditions.{csv,xlsx} file and store the resulting DataFrame object in a variable named cond_df (“conditions dataframe”).

We could start writing our trial loop by now, but this would present the trials just like we defined in the conditions file. Often, you’d want to present the trials in a (semi-)random order. To do so, we can simply shuffle the dataframe, which can be easily done using the sample method of DataFrames using a fraction (frac) of 1:

cond_df = cond_df.sample(frac=1)

This method randomly samples all rows (because frac=1) from the dataframe, which is the same as shuffling it. The next step is to start writing a our trial loop! Because we have a fixed number of trials, we can use a for loop across the rows of our dataframe. The iterrows method of dataframes generates, row by row, the index and the row itself (as a Series object), so it’s perfect for our purposes:

for idx, row in cond_df.iterrows():

# Extract current word and smiley

curr_word = row['word']

curr_smil = row['smiley']

Then, after extracting the smiley and word conditions, we can initialize a TextStim with the current word and an ImageStim with the current smiley and then draw/flip them in a clock-based or frame-based loop, and repeat this process until our trial loop has finished! Important: when using the clock-based timing approach, make sure to reset your clock to 0 at every new iteration/trial (using the clock’s reset method).

ToDo

Try finishing the loop in the previous code snippet as indicated above. You may use either clock-based or frame-based timing. Run the experiment when you’re done!

Click here to show the solution (but try it yourself first!)

for idx, row in cond_df.iterrows():

# Extract current word and smiley

curr_word = row['word']

curr_smil = row['smiley']

# Create and draw text/img

stim_txt = TextStim(win, curr_word, pos=(0, 0.3))

stim_img = ImageStim(win, curr_smil + '.png', )

# Using clock-based timing here

trial_clock.reset()

while trial_clock.getTime() < 2:

# Draw stuff

if trial_clock.getTime() < 0.5:

stim_txt.draw()

stim_img.draw()

else:

fix_target.draw()

win.flip()

Alright, we are 95% done! The trial loop works as expected, but it’s currently not keeping track of any experimental information, like participant responses and stimulus onsets, which is discussed in the next section.

ToDo (optional)

Perhaps twenty trials are a little too few to estimate any meaningful effect … To increase our statistical power (for whatever effect we’re trying to estimate), we can simply repeat our trial loop a number of times (like the nReps property of Builder loops). Try to implement this such that the trial loop is repeated five times. Make sure that each repetition uses a different random order of trials.

Click here to show the solution (but try it yourself first!)

N_REPS = 5 # 5 repetitions for now

for _ in range(N_REPS):

# Shuffle the conditions again!

cond_df = cond_df.sample(frac=1)

for idx, row in cond_df.iterrows():

# Extract current word and smiley

curr_word = row['word']

curr_smil = row['smiley']

# Create and draw text/img

stim_txt = TextStim(win, curr_word, pos=(0, 0.3))

stim_img = ImageStim(win, curr_smil + '.png', )

# Using clock-based timing here

trial_clock.reset()

while trial_clock.getTime() < 2:

# Draw stuff

if trial_clock.getTime() < 0.5:

stim_txt.draw()

stim_img.draw()

else:

fix_target.draw()

win.flip()

Saving responses and stimulus onsets#

After the experimental session, we’d of course like to save some data from the experiment, whether that is just the onsets of the stimuli/trials (like in passive viewing paradigms in neuroimaging) or extensive participant response data (like in psychophysics experiments).

Because the Coder, unlike the Builder, does not save anything by default, we need to save any data we want to store ourselves. One neat way to do so is to use the DataFrame object with the condition info to store information about the trials. For this experiment, let’s keep track and store three things: the participant response for each trial (“left”, “right”, or no keypress), the reaction time for each trial, and the onset of the stimulus.

Let’s start with keeping track of the actual participant response. We’ll, of course, use the Keyboard class as discussed in the previous tutorial.

ToDo (difficult!)

Using a Keyboard object, make sure that both the participant response to each trial (either “left”, “right” or no response) and the reaction time are saved in the conditions DataFrame (i.e., cond_df). Store them in columns with the names response and reaction_time. In case of no response, save the response and reaction time as “n/a”. If there are multiple responses within a trial, make sure to save only the last one. Run the experiment when you’re done to see whether everything works as expected. Bonus: also save whether the response is correct, incorrect, or missing (“n/a”) for each trial (in a column named response_correct).

Hint: to add the data (response/RT) to the cond_df dataframe, use the loc method! You can do these even if the column (response or response_time) does not yet exist!

Click here to show the solution (but try it yourself first!)

# initialize keyboard if not done already

kb = Keyboard()

for idx, row in cond_df.iterrows():

# Extract current word and smiley

curr_word = row['word']

curr_smil = row['smiley']

# Create and draw text/img

stim_txt = TextStim(win, curr_word, pos=(0, 0.3))

stim_img = ImageStim(win, curr_smil + '.png', )

# Set initially to "n/a"

cond_df.loc[idx, "response"] = "n/a"

cond_df.loc[idx, "reaction_time"] = "n/a"

# Using clock-based timing here

trial_clock.reset()

kb.clock.reset()

while trial_clock.getTime() < 2:

# Draw stuff

if trial_clock.getTime() < 0.5:

stim_txt.draw()

stim_img.draw()

else:

fix_target.draw()

win.flip()

# Get responses

keys = kb.getKeys(["left", "right"])

if len(keys) > 0: # if not an empty list ...

# Only pick the last one [-1]

# Overwrite existing data with current one!

cond_df.loc[idx, "response"] = keys[-1].name

cond_df.loc[idx, "reaction_time"] = keys[-1].rt

One last thing that would be nice to save is the onset of each stimulus (i.e., the smiley+word combination) and/or response. For most behavioral experiment this is probably not very interesting, but it is super important for neuroimaging (fMRI, EEG, or MEG) and physiological (eyetracking, ECG, EMG, etc.) experiment in case you want to analyze stimulus-related or response-related correlates in brain or physiological activity! For neuroimaging/physiological data with a high sampling rate (e.g., electrophysiology), you moreover have to be very precise in determining the stimulus onsets, as a difference of a couple of milliseconds may lead to very different effects and their interpretation!

Alright, so it would be nice to save the onsets of our stimuli. But the onset relatively to … what, exactly? In other words, when do we want to start our clock that is going to keep track of the onsets? In case of neuroimaging/physiological studies, this is the moment you start your data acquisition (e.g., the first pulse of your fMRI experiment). At that moment, we would need to reset our clock such that it is in sync with the external data acquisition! We recommend to using a separate clock (a “global clock”, to differentiate it from the “trial clock” we talked about earlier) to keep track of the stimulus onsets.

Then, assuming our clock has been reset at the appropriate moment, how do we make sure we save the stimulus onset only after the first flip? There are actually many ways in which you could do this!

ToDo

Try to think of a way to save the onset of each stimulus (in the cond_df dataframe) after the first flip and implement this in your script. You may use the global clock (the clock variable) we defined in the previous tutorial. Make sure to reset it before the trial loop! Also, after the end of the loop, make sure to save the cond_df dataframe to disk with the name: sub-{participant nr}_events.csv (where participant nr refers to the value from the dialog box).

Click here to show the solution (but try it yourself first!)

# We left out the response/RT part for clarity

# Reset "global" clock!

clock.reset()

for idx, row in cond_df.iterrows():

# Extract current word and smiley

curr_word = row['word']

curr_smil = row['smiley']

# Create and draw text/img

stim_txt = TextStim(win, curr_word, pos=(0, 0.3))

stim_img = ImageStim(win, curr_smil + '.png', )

# Initialize with None, which will be overwritten on

# the first flip

onset = None

trial_clock.reset()

while trial_clock.getTime() < 2:

if trial_clock.getTime() < 0.5:

stim_txt.draw()

stim_img.draw()

else:

fix_target.draw()

win.flip()

# Get onset only after the first flip!

if onset is None:

onset = clock.getTime()

Non-slip timing (optional)#

If you managed to implement the last ToDo and you inspected the saved logfile, you might have noticed that the onsets seem to increase with a little more than 2 seconds. This inconsistency likely comes from the fact that the while loop we used to control the trial duration probably does not end neatly before the next screen refresh. Another reason is that the initialization of the new TextStim and ImageStim takes a little time that causes the routine to take a little longer than two seconds.

For most experiments, this issue is not really important, but for fMRI experiments it actually may be! This is because the data acquisition of fMRI scans is often predetermined (e.g., 250 “MRI volumes” of 2 seconds each → 500 seconds) and this issue may cause the experiment to “overshoot” the actual data acquisition (read more about this issue here).

To fix this “overshoot” issue, we need to compensate for the inaccuracies in our stimulus/trial durations; this is sometimes called non-slip timing. One way we can compensate these “overshoots” is using the clock itself. Instead of using it as a “stopwatch” (looping until it has reached a value), we can use it as a “timer” (looping until it has no time left anymore). This can be done using the add method of Clock objects, which (paradoxically) subtract time from the clock. For example, if you’d call add(2) right after resetting a clock, getTime would return approximately -2. Using this approach, we could subsequently loop until the clock is at 0, at which point we know the routine took 2 seconds. Any “overshoot” will then automatically be corrected for in the next routine.

Written out in code, this would look something like the following:

clock.reset()

for i in range(10):

# Set the clock to approx. -2 seconds

clock.add(2)

# Do some stuff, like initializing components

# ...

# Loop until clock is at 0

while clock < 0:

pass # do stuff

ToDo (optional)

Try implementing this non-slip timing approach in your emotion-word Stroop experiment. Then, run the experiment and check the resulting logfile. Is the overshoot issue fixed?

Wrapping up#

Okay, that will have to do for this Coder tutorial. We discussed how to implement the most important experiment features using the psychopy package, but the package offers much more than we discussed here (such as auditory components, colorspaces, array stimuli, rating stimuli, and eyetracker integration). We leave this up to you to explore on your own. On the next page, we included some resources to help you with this.